At the 2007 Climate Change Conference, held in Bali, negotiators agreed that REDD – reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation – should be a key component of the agreement that will replace the Kyoto Protocol in 2012. Deforestation accounts for approximately 20% of greenhouse gas emissions and reducing the rate at which forests are cleared will cut emissions.

While fully supporting REDD, the Centre believes it needs to go further to consider agricultural landscapes beyond the forest boundaries. “During the past year, we have tried to move the agenda beyond REDD,” explains Frank Place, Head of the World Agroforestry Centre’s Impact Office. “The key focus of REDD is tackling emissions by planting or protecting forests, but it fails to recognize the role farmers can play in sequestering carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.”

A whole landscape approach

The potential for extending REDD was highlighted by the World Agroforestry Centre when the 14th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change met in Poland in 2008. The Norwegian Government subsequently accepted World Agroforestry Centre scientist Meine van Noordwijk’s proposal to develop the concept further. Instead of just reducing emissions from deforestation and degradation, he argues, we need to reduce emissions from all land uses – REALU, for short.

One of the difficulties with REDD relates to the definition of what is, and is not, forest, and this is largely determined by institutional arrangements rather than tree cover. Take, for example, Indonesia, the world’s third largest emitter of greenhouse gases. According to van Noordwijk, you will find large areas of land classified as ‘forest’ without any trees, and large areas of ‘non-forest’ with significant tree cover. REDD would only apply to the land classified as ‘forest’, even though the ‘non-forest’ areas that actually have tree cover are highly significant when it comes to their greenhouse gas emissions, and could potentially play a major role in sequestering carbon.

At a rough estimate, REDD projects will only capture, at best, 60–70% of the emissions related to land-use change. “If we really want to reduce land-use emissions,” says van Noordwijk, “we need to capture the other 30–40% as well, and much of that can be done by developing smallholder agroforestry on land which is not classified as forest land.” In other words, we need REALU, which goes beyond REDD.

Most of the deforestation in Africa, and in many parts of Asia, is caused by agricultural expansion, largely by smallholder farmers. This means they can’t be ignored in a future climate change agreement. “If millions of smallholders are denied access to the carbon market, then there’ll be no incentive for them to change the way they behave,” says Peter Minang, Global Coordinator of the ASB Partnership for the Tropical Forest Margins.

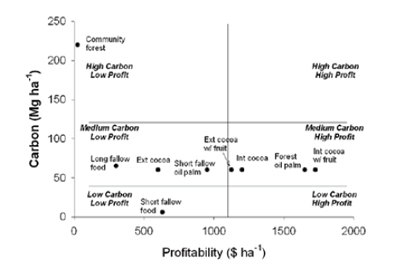

Drawing on over a decade of research on the complex relationship between forests and the adjacent landscapes, Minang and his colleagues believe that REDD is unlikely to achieve significant emission reductions unless it explicitly includes arrangements which encourage farmers to plant trees. “We should be encouraging carbon-rich agroforestry,” says Minang. “It has the potential to increase farmers’ income, sequester more carbon and benefit biodiversity.” The ASB Policy Brief REDD Strategies for High Carbon Rural Development describes the benefits – both for climate mitigation and local livelihoods – of agroforestry.

A new initiative for Africa

Research conducted by ASB found that in 80% of the areas investigated, the activities that caused a loss of carbon, such as converting forests to cropland, generated USD 5 or less in profits for every tonne of CO2 equivalent released. This is considerably less than some of the current prices being payed for carbon, for example when traded under the EU’s Emission Trading System. This means that relatively modest payments could deter farmers from clearing forests and at the same time encourage them to plant tree crops.

This could be particularly important in Africa. Between 1900 and 2005, more than 9% of Africa’s forests were lost, at a rate of 4 million hectares a year. If this continues, greenhouse gas emissions from African agriculture could increase by more than 60% by 2030.

Preventing this, and helping African smallholders benefit from the carbon trade, is a key objective of the Africa Biocarbon Initiative, established by the Common Market for East and Southern Africa (COMESA). The World Agroforestry Centre is providing scientific evidence to support the initiative. “The initiative is helping African governments engage in climate-change issues in a way they never did before,” explains Minang. “It has created an African voice, and that’s very important when it comes to international negotiations.”

During the past year, the World Agroforestry Centre convened 11 COMESA workshops, bringing together policy makers, scientists and other interested parties from the 19 member countries. Together, they developed a clear idea of what they wanted from the Copenhagen climate meeting: an agreement that takes decisive action to reduce emissions and increase carbon stocks not just on forest land, but on land used for other purposes as well.

Getting the sums right

One of the reasons why agricultural landscapes have been excluded from the EU’s Emission Trading System relates to the difficulties in measuring carbon stocks. “The argument is that it’s possible to measure the amount of carbon in a large, uniform tree plantation in, say, Moldova,” explains Jonathan Haskett, principal scientist at the World Agroforestry Centre, “but we don’t know how to measure carbon stocks in a landscape where there is a mosaic of different land uses, and trees are scattered in blocks of different sizes and species.”

This is all set to change. Scientists from the World Agroforestry Centre, the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), Michigan State University and World Wildlife Fund (WWF) are developing a new system to measure, monitor and manage carbon in a diverse range of landscapes. The research is being carried out under the Carbon Benefits Project, funded by the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and the United Nations Environment Programme. The project includes research sites in Kenya, Niger, Nigeria and China.

GEF was particularly keen to fund the research as it will provide the sort of guidance it needs to calculate the carbon benefits of the development projects it funds. “Although we’re still developing the system for measuring carbon in complex landscapes, GEF is interested in applying the system across a wide range of land use projects in its portfolio,” says Haskett. “This project is putting an end to the idea that you can’t measure carbon beyond large blocks of forests.”

Combining remote sensing, infrared spectroscopy (see page 17) and rigorous statistical analysis, the research could remove one of the major barriers which prevents smallholder farmers engaging in the carbon market. |